An Appreciation of Richard Collin- the late New Orleans restaurant critic & cookbook author

and his use of mace, along with a related discussion of the fricassee.

Richard Collin, adopted son of New Orleans and keeper of its living and lively culinary heritage, died last month at the age of 78. Collin was the city’s first food critic, and his New Orleans Underground Gourmet, first published in 1970 and continuously updated since then, has been so reliable and enjoyable that he has “had a cult following; one found his book, dog-eared and gravy stained, next to the phone book in houses all over the Crescent City.” (Independent) Even the Editor, then based in New York, had a copy during the 1990s.

Despite his stature, notice of Collin’s passing has not appeared anywhere outside of Louisiana (until now). Depending on your perspective, that observation is evidence of either unjustifiable neglect or the persistence of American regional foodways. Either way, it reflects the unique, and uniquely unknown, culture of New Orleans.

In a city that has worshipped food since its foundation, no newspaper enlisted a restaurant critic until 1972. It was Collin himself, chosen by Charles Ferguson, then editor of the New Orleans States-Item (since merged into the Times-Picayune) based on his wife’s suggestion, which in turn was based solely on the Underground Gourmet.

Collin wielded immense power. According to Ferguson, “[h]e was the first and in many ways the most influential” of a now considerable number of critics, in and beyond New Orleans, who have assessed its restaurants. When Collin began his column, Ferguson adds, “we thought we were a restaurant town. But the profusion of really good restaurants occurred after he became the critic. It was the first time New Orleans restaurants had been held to a standard of performance. He had pretty strong views and didn’t mince words.” (Independent)

Collin was an unusual choice. An outsider to an insular culture dominated by ossified elites, he came to New Orleans from Philadelphia almost by accident. His employer, a book distributor, assigned New Orleans as part of his territory; and like thousands of other accidental visitors, Collin and his wife Rima fell in love with the place and its food. He tried to find a job and despite the lack of any teaching experience landed one as a Professor of History at the University of New Orleans. (Times-Picayune)

He must have had a prescient interviewer because things worked out for everyone. Collin went on to publish authoritative work on the Caribbean policy of Theodore Roosevelt and became “a magnificent teacher, very dramatic. Oftentimes he would wear costumes to class and cut up. Any of the students you talk to really loved him, a lot more than the restaurants did.” (Times-Picayune)

He must have had a prescient interviewer because things worked out for everyone. Collin went on to publish authoritative work on the Caribbean policy of Theodore Roosevelt and became “a magnificent teacher, very dramatic. Oftentimes he would wear costumes to class and cut up. Any of the students you talk to really loved him, a lot more than the restaurants did.” (Times-Picayune)

There is no little irony in remembering Collin in the same number that assesses the life of Elizabeth David for, as all of this indicates, he was the antiDavid. Gerald Bodet, a fellow UNO professor, called Collin “a great scholar and bon vivant, a great colleague.” (Times-Picayune) Despite his work on Roosevelt, Collin “specialized in culture, music and art” according to Raphael Cassimere, another colleague, simply, we suspect, out of sheer joy. “He was very playful and liked to have fun.” (Cassimere again, quoted in the Times-Picayune)

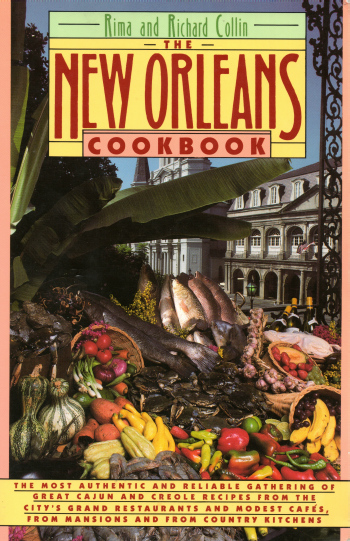

In further contrast to David, Collin remained devoted to his spouse, and after her death published a moving memoir about their life together and her last months, Travels With Rima. They considered themselves ‘oddball academics’ and she not only served on the UNO faculty (professor of comparative literature) like her husband but also collaborated with him on what we consider his most important work: The New Orleans Cookbook. It has exerted a great influence on people who cook Louisiana food, including the Editor, and was among the three bestselling cookbooks purchased in 2006 by New Orleanians restocking their kitchen collections after Katrina. (Times-Picayune) That is fitting: The Collins dedicated their book to “the city and the people of New Orleans.” The book has undergone more than ten revisions since its publication in 1975 and it too remains in print.

In further contrast to David, Collin remained devoted to his spouse, and after her death published a moving memoir about their life together and her last months, Travels With Rima. They considered themselves ‘oddball academics’ and she not only served on the UNO faculty (professor of comparative literature) like her husband but also collaborated with him on what we consider his most important work: The New Orleans Cookbook. It has exerted a great influence on people who cook Louisiana food, including the Editor, and was among the three bestselling cookbooks purchased in 2006 by New Orleanians restocking their kitchen collections after Katrina. (Times-Picayune) That is fitting: The Collins dedicated their book to “the city and the people of New Orleans.” The book has undergone more than ten revisions since its publication in 1975 and it too remains in print.

If the life and work of Richard Collin seem unrelated to British foodways, that appearance is deceptive. The distinctive cuisines of New Orleans, plural because Cajun and ‘new Louisiana’ have joined Creole technique as unique staples in the eccentric city, draw from many origins. French influence is not predominant, despite the prevalent mythology, and it would not be outlandish to contend that in broader cultural terms, the persistence of the language in Louisiana is coincidental more than influential.

West Africa, the Caribbean and especially St. Domingue (Haiti since 1804), Germany, Spain, native Americans and what was the Acadian region of eastern Canada, as well as France, have been culinary influences on New Orleans. British food is not ordinarily considered one of them in the popular imagination, but John Folse, who devotes a chapter to English antecedents in his Encyclopedia of Cajun & Creole Cuisine, and others have made the case. It is buttressed by the Collins’ book.

One recipe, for the peacemaker or oyster loaf, originated as a ubiquitous London street food long before the founding of New Orleans in 1718, and a scholarly consensus holds that this New Orleans classic arrived via the Thames. (See, e.g., Grigson 110: “It was taken to America, and became popular in New Orleans, where it acquired the endearing name of la mediatrice.”) The combination of duck and turnips in another recipe from the Cookbook is traditional to British cooking too. (See, e.g., Duck with Bacon and Turnips with Oranges in the practical)

Fricassees provide another example. The word itself comes from Middle French and may be derivative of the Latin words for ‘fry’ and ‘cut.’ When prepared with a roux, fricassee has become associated with Cajun foodways, but the dish itself originated in England, where it had fallen from favor by the middle of the nineteenth century. Eliza Acton, for example, included only one recipe in Modern Cookery for Private Families, her encyclopedic assembly of English recipes.

Fricassees provide another example. The word itself comes from Middle French and may be derivative of the Latin words for ‘fry’ and ‘cut.’ When prepared with a roux, fricassee has become associated with Cajun foodways, but the dish itself originated in England, where it had fallen from favor by the middle of the nineteenth century. Eliza Acton, for example, included only one recipe in Modern Cookery for Private Families, her encyclopedic assembly of English recipes.

Back to the origins of the dish, a recipe, for “Frigasie of Chickens,” appears in print at least as early as 1653. (Gentlewoman’s Delight) According to Gilly Lehmann, it arose not from a French translation but rather from an English kitchen manuscript. (Housewife 38, 43) As she notes, “… the use of the French word was a linguistic rather than a culinary borrowing.” (“Olios” 69) “In spite of its name, the fricassee was more English than French.” (“Olios” 74)

Despite the appearance of the term in print nearly a century earlier, the 1653 recipe marks the dawn of the modern dish. “What we know as a fricassee was beginning to emerge: meat, usually chicken, fried and then stewed in a sauce which was then thickened at the end of the cooking time.” (“Olios” 69)

The Collins include fricassees of both chicken and duck. Writing about the chicken variant four years ago in her own (unpublished) British cookery manuscript, the Editor noted that her version “derives from the excellent New Orleans Cookbook by Rima and Richard Collins: The reference is no typographical error, because as the recipe’s name and its use of cayenne, mace, turmeric and Worcestershire together indicate, Britain has contributed to the foodways of Louisiana.”

As further evidence, the Collins’ fricassee shares a relative simplicity with the older English recipes. Twentieth century versions typically add mushrooms and flavorings absent from the Collins’, but while they explain that “[a]t the turn of the century, Creole cooks prepared chicken this way,” the Editor has been unable to find evidence of mace in other savory Creole recipes or of turmeric in traditional Louisiana recipes at all. (Collin 147) Until now, the spicing of the dish, one of our favorites at britshfoodinamerica, had puzzled us.

It turns out that the parents of Richard Collin were Londoners. (Independent; Times-Picayune)

***

Recipes for chicken fricassees, along with the eighteenth-century recipe of Hannah Glasse for a mushroom fricassee, appear in the practical.

Editor’s note.

We had intended to post an appreciation of Nicholas Culpeper in connection with our Elizabeth David number, but changed our plans after learning of Mr. Collin’s death. An assessment of the influences shaping David’s outlook, including within it an appreciation of Culpeper, will appear in a subsequent number.

Sources.

Eliza Acton, Modern Cookery for Private Families (London 1855)

Richard Collin, Travels With Rima (Baton Rouge 2002)

Rima and Richard Collin, The New Orleans Cookbook (New York 1975)

John Folse, The Encyclopedia of Cajun & Creole Cuisine (Gonzales, Louisiana 2004)

Jane Grigson, English Food (London 1974)

‘W. J.’, A True Gentlewoman’s Delight (London 1653)

Gilly Lehmann, The British Housewife (Totnes, Devon 2003);

“Olios and Fricassees,” in Eileen White (ed.), The English Kitchen (Totnes, Devon 2007)

Mary Tutwiler, “Underground Gourmet Richard Collin remembered,” The Independent Weekly (Lafayette, Louisiana, 26 January 2010)

Judy Walker, “Richard H. Collin, ‘the New Orleans underground gourmet,’ dies at age 78,” The Times Picayune (22 January 2010)