Portman Pudding & Snoek Piquant:

Our Guest Historian chronicles the rise, rise and fall of the ration book in midcentury Britain.

The word “austerity” has a number of meanings: harshness, abstinence and severe simplicity or lack of adornment. In Britain it was widely used during the Second World War and its aftermath to describe food, clothes, soap and other goods stripped to their essentials. This period in British history, running broadly between 1939 when war broke out, and 1954 when the last food items (butter, margarine, cooking fats and meat) ceased to be rationed, is often termed “the age of austerity”.

In 2000 Oxford University Press published Ina Zweiniger-Bargielowska’s comprehensive and prize-winning Austerity in Britain. Rationing, Controls and Consumption, 1939-1955. The phrase has also been employed to describe the post-war period between 1945 and 1951: The Age of Austerity, 1945-51, a collection of essays edited by Michael Sissons and Philip French, appeared as long ago as 1963, and 2007 saw the publication of David Kynaston’s Austerity Britain, 1945-51.

Recently the term has re-entered everyday speech to describe the hard times predicted for the second decade of the twenty-first century as a result of the banking crisis, public debt, business retrenchment, high rates of unemployment and severe cuts in government expenditure. In October 2010 Britain’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne, warned, not for the first time, of an impending “new age of austerity”. So far and for the foreseeable future, however, a return to the “make do and mend” culture and the mass privations of the 1940s and early 1950s remain out of the question.

This essay discusses the real “age of austerity” in the forties and early fifties. During the years of conflict, with the economy on a war footing, a country long lacking in economic self-sufficiency depended more than ever on imports for its survival. Yet for much of the war convoys carrying those goods from the United States and elsewhere suffered grave losses from submarine attack. The extension of austerity deep into the post-war period reflected the parlous state of the economy after nearly six years of total war. Though one of the victor nations, Britain’s material state resembled that of a loser for, as Andrew Marr has written, “the country was broke”. (A History of Modern Britain, London 2007, 10)

When the diarist Nella Last and her husband strolled around Morecambe, Lancashire, in the summer of 1945 they marvelled “at the tons of good food--things in Marks and Spencer’s like brawn and sausage, thousands of sausage rolls and pies, including big raised pork pies”. (quoted in Kynaston 85) Others noted the reappearance of bananas (for children only--few of whom had ever seen one or had any idea how to deal with them). Semolina, sultanas [Editor’s note: raisins] and mustard also were on offer to a greater extent.

Few expected a rapid return to pre-war abundance and variety, but hopes were high for gradual improvement. In the event the return of peace saw things deteriorate with meat, for example, becoming scarcer than it had been even at the height of the war. Abrupt termination of America’s Lend-Lease programme in August 1945 cut off the aid on which Britain (and other countries) had come to depend. Dried egg, a wartime staple, disappeared from the shops. Then, to public consternation, bread was added to the ration. In an effort to redirect resources and prevent starvation in Asia, it remained rationed between 1946 and 1948. Even potatoes became rationed in 1947. Cuts to bacon, poultry and egg rations were introduced in February 1946 and the arrival from South Africa of millions of cans of unpalatable ‘snoek’ (a large barracuda-like oily fish) in May 1948 provided scant compensation. Supposedly, an ungrateful nation fed much of this ‘delicacy’ to cats.

Cuts continued; by 1948 food rations were substantially lower than they had been at any time during the war. Amid all the hardship was a variety of other miseries: shortfalls in housing, coal and electricity, along with the harshest winter of the century in 1946-47. Only when the Marshall Plan for the economic recovery of Europe (including Britain) kicked in during 1948 did things begin to improve. Nevertheless, by the end of the decade the British Medical Association, which had been sanguine about the nation’s wartime diet, warned about the increased difficulty of obtaining sufficient and appetising food since the cessation of hostilities.

Food controls were slowly eased in the early 1950s. Milk rationing ended in January 1950; flour and eggs were de-rationed in the autumn. But there was still a way to go; between autumn 1953 and spring 1954, the final food items of sugar, bacon, ham, cheese, fats and fresh meat were de-rationed. A consumer boom followed. As early as 20 July 1957 Prime Minister Harold Macmillan felt able to pronounce in a speech at Bedford that “most of our people have never had it so good”.

********

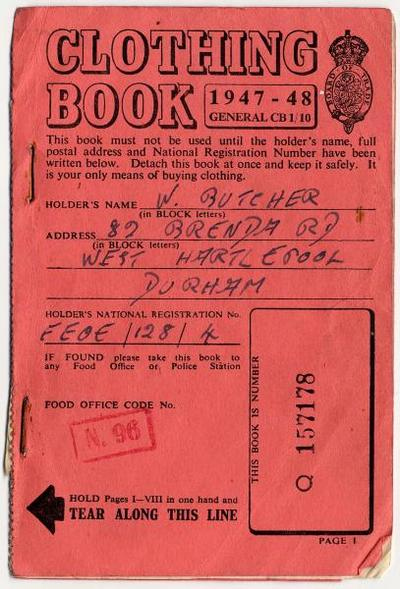

The Ministry of Food distributed ration books in 1939 but the programme did not begin until January 1940 when sugar, butter and bacon became the first rationed foods. Meat, tea, margarine and cooking fat had all followed by July. Later, milk, tea, eggs and preserves were added. Except for tea, which could be purchased anywhere, consumers were obliged to register with particular retailers, who in turn had to register with wholesalers. Ration regulations varied according to availability but, broadly, one adult was entitled to purchase small quantities of basic foods: Two small chops, one egg, two ounces of butter, two ounces of cheese, two ounces of tea per week. From December 1941 certain foods were allotted a points value. Everyone acquired a small monthly allocation of points that could be used, according to choice, to purchase additional items--the scarcer the item, the more points needed to obtain it. In all cases an entitlement to purchase did not necessarily mean, at any given point, that all foodstuffs would be available. For women in particular, who still bore the brunt of domestic management, food shopping therefore could mean hours of queuing.

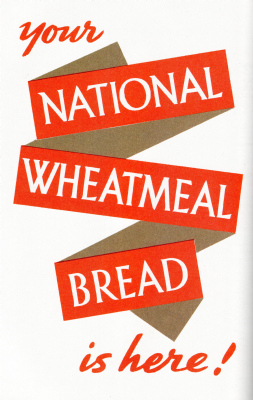

Bread may not have been rationed until after the war, but the enthusiastically promoted “national wholemeal loaf” which replaced white bread was widely disliked. The personal cultivation of vegetables was the subject of unremitting propaganda, especially via the famous ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign, and home grown fresh fruit never was rationed. Neither was fish; the national dish, fish and chips, or other restaurant meals never were subject to rationing either. Offal and sausages were rationed, but only between 1942 and 1944. None of this meant that particular items remained plentiful. Onions disappeared from shops with the fall of France and capture of the Channel Islands, peas became mysteriously unavailable and some grocers discarded items like tomatoes (or spirited them onto the black market) rather than take a loss by selling them at the artificially low levels set by wartime price controls.

The government, often in the person of the widely admired Lord Woolton, Minister for Food between 1940 and 1943, constantly offered food “tips”. For example, it enjoined people to beat the ration by gathering free food in the form of rosehips for marmalade, crab apples for jam, chestnuts to roast and blackberries for puddings and jelly. Those who lived near the sea were encouraged to collect seaweed, shellfish, cormorants’ eggs and even the cormorants themselves. Wartime magazines were another source of advice. Good Housekeeping, for example, urged its readers not to ignore the culinary potential of squirrels and hedgehogs: “[Y]ou will find them both good to eat”. (Women 48)

Rationing involved a large bureaucracy and complex system of food distibution that included registrations, government subsidies and price controls. It also spawned a range of criminal activity, including the theft and counterfeiting of ration books. Foodstuffs generally were too bulky and too low in value to provide much attraction to organised criminals. They could make more money from clothing such as nylon stockings. But a “black market” in food did arise during and after the war, notwithstanding all the prosecutions and other enforcement efforts of the Ministry of Food. The word “spiv”, meaning a petty crook without regular employment who lived on his wits, was current before the war but soon came to be particularly associated with flashy dressers who, for a consideration, could conjure half a dozen eggs or a few rashers of bacon.

Though not without widespread grumbling, rationing was widely recognised as ‘fair’, insomuch as it guaranteed a sufficiency of nutritious food for all, even the poorest sections of society. A perception of fairness was important in terms of morale in a total war that required the mobilisation of the entire population. It encouraged those suffering privation to know that even for MPs dining in the House of Commons, the only meat available was seal and whale. (Kynaston 105) In the interest of demonstrable fairness, King George VI had his own ration book. Of course, he and others at the top of the social scale also had access to landed estates holding vast quantities of unrationed fish and game and, when one of his subjects observed the queen at close quarters in 1945, she noted how “well fed” Her Majesty looked “considering the rationing”. (Kynaston 105) In fact, luxury foods such as shellfish and venison never were rationed owing to limited supplies. For those who could afford high prices they remained readily available throughout the war--as the diaries of Harold Nicholson and “Chips” Channon indicate. Popular perception about the “lavish eating” of the rich gave rise to a degree of resentment. (Zweiniger-Bargielowska 78)

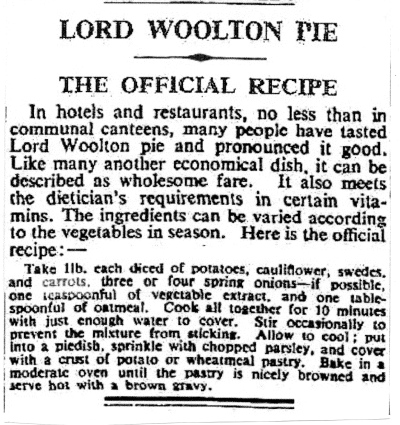

For the majority, rationing and food shortages in general led to a dull diet featuring dishes such as Portman Pudding (“a sweet that needs little sugar”) and, perhaps most famously, meatless “Woolton Pie”. It first appeared on the menu of the Savoy Grill as “Le Lord Woolton Pie” and was reviled. An admirer of Lord Woolton declared “I just can’t believe that such a wonderful man could have given his name to such a dish”. (Ministry 86)

from The Times, 26 April 1941

They loved the Lord but not his pie.

The “Boston Bake” of white beans, fat bacon, carrots, mustard and golden syrup, however, does sound “delicious” as advertised and should be recognisable to any Yankee as a slight variation on traditional baked beans. It was also allegedly good for seeing better in the blackout. Towards the end of the war many Britons had become virtual vegetarians--though not by choice. But if only because bread and potatoes are filling, no one needed to go hungry.

For the millions who had been impoverished and undernourished in the 1930s, the wartime diet represented a dramatic improvement. There is some truth to Lord Woolton’s comment from 1941 that the nation had not been in such good health for years. Since the war it has become something of a cliché that the British diet never has been as healthy as it was under rationing when Britons had more or less the same calorie intake as today but obtained far fewer of them from sugars and animal fats.

In 1988 the historian Peter Hennessy tried living for a week on the rations that had been available to an adult for the last week of the war. With one lapse (a piece of banana cake) he adhered to the regimen and afterwards reported that he suffered food boredom and lost two pounds in weight but never felt hungry. At the same time he recognised that the experiment was unrealistic since he was healthy and well nourished when he embarked on it. Neither did he perform any manual labour throughout its duration. Even so he believed he gained some understanding of the pleasure that an ‘off ration’ treat must have brought and also of how an entire nation became obsessed with food. (Hennessy 50)

In 2007 the Daily Mail conducted a similar exercise with a family of six in an effort to answer the question: “Can a modern family survive on wartime rations?” Prompted by the obesity crisis and consequential health problems (including an upsurge in diabetes, strokes, heart disease and some forms of cancer), the newspaper sought to ascertain whether reintroduction of wartime dining patterns would supply a better solution to poor eating habits than the fad diets and surgery to which many were resorting.

The participant family’s normal diet consisted of a high degree of processed, ready-to-eat food. At the end of the exercise the parents reported back in favourable terms. With no junk food, snacks or treats on the weekly shopping list, household expenditure on food was slashed by around 50 per cent. Because they were unable to snack between meals they came to the dining table hungry and wasted nothing. They enjoyed the food, including its manual preparation, consumed many more vegetables than usual, lost a little weight, found their energy levels much increased and experienced more regular bowel movements. The four child participants, aged between 2 and 8, were less enthusiastic but their mother reported that they became slimmer, more active, less ‘hyper’ and less fractious. They also slept better. The nutritionist associated with the project found none of these results surprising. He conceded, however, that the wartime diet lacked ‘the variety and choice that makes eating an enjoyable, pleasurable experience’ so the overall conclusion supported increased consumption of a varied diet consisting of home-prepared foods high in fibre along with a reduced intake of highly-refined sugary or salty snacks.

Anyway, I’m off now for some ‘snoek piquante’ (see recipe below) and reconstituted egg followed by a slice or two of pig’s head pudding.

********

Snoek Piquante

Ingredients: 4 spring onions chopped, liquid from the snoek can, 4 Tablespoons of vinegar, ½ can of mashed snoek, 2 teaspoons of syrup, salt and pepper.

Directions: Cook onions in snoek liquor and vinegar for 5 minutes. Add all other ingredients and mix well. Serve cold with a salad.

Sources:

Jane Fearnley-Whittingstall, The Ministry of Food: Thrifty Wartime Ways to Feed your Family Today (London 2010)

Peter Hennessy, Never Again: Britain, 1945-1951 (London1992)

David Kynaston, Austerity Britain, 1945-51 (London 2007)

Michael Sisson & Phillip French (eds.), The Age of Austerity, 1945-51 (London 1963)

Jane Waller & Michael Vaughan-Rees, Women in Wartime: The Role of Women’s Magazines, 1939-1945 (London 1987)

Ina Zweiniger-Bargielowska, Austerity in Britain: Rationing, Controls and Consumption, 1939-1955(Oxford 2000)