It happened in Vermont: An unlikely time & place of publication.

1. A turn to culinary tradition at the dawn of the swinging sixties.

A cookbook on an unlikely topic appeared during 1960 in the United States. It did not enjoy a second edition and is forgotten, no surprise on either count because the book addressed British foodways. It was a fearless but hopeless effort worthy of attention at this long remove.

The reputation of British food may have reached a nadir even in its country of origin at the time this book appeared despite the tenth anniversary of The Good Food Guide . The Guide started out extolling plain British food, and even distinguished the English from the Scottish culinary style in conformity with the taste of its founder, the delightful Raymond Postgate. As the influence of Elizabeth David relegated British food to untouchable status, however, the Guide began to reflect the national taste and restaurants serving British dishes receded from its list of recommendations.

If British cuisine never quite died away in Britain, it became the butt of ridicule in the United States, where one of the most robust and consequential cuisines in global history remains nearly unknown.

2. A professor from Vermont makes her case.

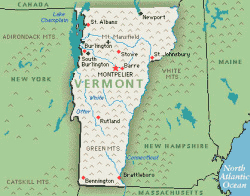

The book at issue reflects that reality with its title, In Defense of British Cooking: 200 Wonderful Recipes that prove the English CAN cook. Its place of publication was unlikely. Brattleboro, Vermont, was and is no cosmopolis, although unlike lots of bigger cities beyond New England it can claim a bookstore, in fact four of them, two specializing in used volumes. Along with used bookstores, traditional British foodways have lingered longer in New England than elsewhere in the United States, but it is superficially surprising to see how so deviant a subject found its voice in northern New England at the dawn of the sixties.

Swinging ‘60s Vermont

Unless, that is, a professor from a small local college came to the attention, or brought herself to the attention, of a small local press. It could not happen now but that is what happened then to Audrey Alley Gorton, author of In Defense. Not much is known about her. She wrote only one other book, itself more a pamphlet on the intricacies of shooting, dressing and cooking deer, which ironically enough is cited with greater frequently than the longer one on British food.

We do know from In Defense of British Cooking that Gorton broadcast at some point on the BBC and wrote for the Guardian while living in England. She was not a native but rather had followed an English husband there from Boston. After her stint of undetermined time in England following World War Two, she taught English for years at Marlboro College, a progressive institution with a fluctuating enrollment of no more than three hundred students. ( see Gorton 7)

Gorton must have been a beloved figure. The college confers its annual

“Audrey Alley Gorton award, given in memory of Audrey Gorton, Marlboro alumna and member of the faculty for 33 years, to the students who best reflect the Gorton qualities of: passion for reading, an independence of critical judgment, fastidious attention to matters of style, and a gift for intelligent conversation.” (potash)

Based on the evidence of In Defense and despite its flaws, the trustees of the College chose well in naming the prize for Gorton. We only can presume her passion for reading at this point, but choosing to champion British food in America during 1960 displays nothing if not independent judgment, while the style of her introduction is indeed fastidious and conversational in a pleasant rather than cloying or hectoring way.

3. Is it Blair?

Gorton does not say so, but her title evokes “In Defence of English Cooking,” the essay Orwell wrote for the London Evening Standard during 1945. Did she know? We cannot tell, but Gorton did live in England after the war, was (apparently) that voracious reader and taught literature at the time she wrote her own Defense .

Gorton does not say so, but her title evokes “In Defence of English Cooking,” the essay Orwell wrote for the London Evening Standard during 1945. Did she know? We cannot tell, but Gorton did live in England after the war, was (apparently) that voracious reader and taught literature at the time she wrote her own Defense .

The tone of the book tracks its insistent title. As Gorton explains, her

“aggressive attitude on the subject of English cooking--this doubling of my fists in anticipation of attack--is the result of the raised eyebrows, the facetious comments, or the general surprise that greet the admission that I am working on an English cookbook.” (Gorton 2)

Plus ça change . Anybody working in the British culinary idiom on American soil today has endured the same treatment despite beachheads of informal British cooking like Owen & Engine in Chicago and the Peacock in New York.

It is unjustified now as Gorton claims it was then, and largely emanates from the same disqualified source. “These reactions are not limited to those who have actually eaten three (or four) meals a day in England, but are assumed to be the peculiar privilege of all and sundry.” (Gorton 2-3)

4. The destruction of British foodways.

Gorton herself would not deny that cooking in Britain had devolved into dire straits. She blames the decline on several sound factors, including the first Industrial Revolution. “Town dwellers, cut off by low incomes from the vegetables and fruits and dairy products obtainable in the country, fell back on the only fare they could afford” in the form of “bread, potatoes and tea.” (Gorton 6-7)

The interwar “years of unemployment,” as Gorton delicately describes the Great Depression, deepened the dive. “Food became class-differentiated.” Then came the Second World War, fifteen years of austerity and “the heroic restraint of the British” in culinary terms. That restraint, claims Gorton, cannot be equated with idle acquiescence. It was no “indication that they didn’t know what they were missing--or didn’t long for a decent meal.” (Gorton 7)

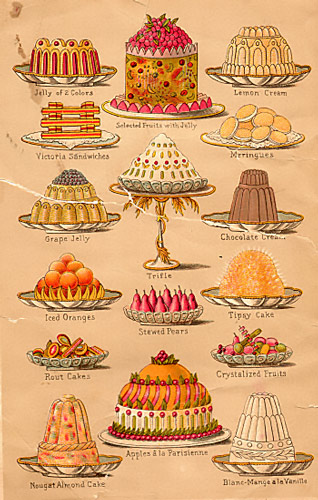

Gorton argues, not unreasonably, that she should know because she was there, and “was not the only one who gagged on the dried-egg omelettes and the weekly ration of ‘old ewe’” imposed by rationing writ large on an increasingly restive population. As she notes, before industrialization, urban impoverishment and the wars of the twentieth century, “English cooking [was] traditionally based on an economy of abundance” encompassing not just a lot of John Bull meat. British kitchens also prepared fish and shellfish, freshwater and salt, fresh and cured; all manner of berries and other northern fruits; vegetables so good a British cook would not dare dress them up in more than butter, pepper and salt; and uniquely British “[b]uns, cakes and tarts; trifles, syllabubs, savouries… ” (Gorton 7)

5. British food in America.

Although we have no evidence she knew about the work of Florence White, Gorton like her forebear noticed an enduring culinary bond between Britain and America. Historically, “English cooking follows a pattern similar to our own.” Then, however, she gets the pattern wrong.

Gorton repeats the evergreen misapprehension that British food always has been bland. With the exception of curries,” she claims, “there is little highly spiced food. ‘Salt and pepper to taste’ are the usual directions for seasoning.” (Gorton 8) As readers of britishfoodinamerica and any number of other sources understand, British kitchens teemed with herbs fresh and dried, and the great trading nation imported all manner of spice at least as early as the seventeenth century. Flavorings of anchovy and oyster enhance a lot of pies, puddings and stews: The list of elements contributing to the high seasoning of traditional British cuisine is long.

Part of her misapprehension may stem from a measure of self-selection, for Gorton herself likes mild flavors. In her opinion, “it is surprising how good one’s food tastes without the pinch of this and that currently fashionable” in 1960 America. (Gorton 8)

She describes a number of good simple dishes. None of them will faze the novice, a very good thing. Ham cake, not much more than meat, bread and ale, is plain and pleasing, although its omission from the index does make it hard to find (go to page 53). Her Lancashire Hot Pot layered with lamb, onion and potato includes the traditional, game-changing oysters excised by too many modern writers. She also fashions an appealing variation on shortbread previously unknown to the Editor from oatmeal instead of flour and boosted with ginger.

Nearly nobody else beside the uneven Nell Heaton and comprehensive Elisabeth Ayrton would remember kidney cooked in a casing of onion, and Gorton’s recipe is just as good as theirs. It was a staple supper in Royal Navy towns. Sailors brought their rum ration (or perhaps a portion of the ration) to bakers who simmered the savory globes in a bath of stock and rum.

6. Flaws in a system.

Unfortunately many of the recipes Gorton has compiled are not so wonderful, and represent minimalist shadows of robust traditional preparations. Her Melton Mowbray pork pie lacks the essential anchovy along with bacon or sage and will not work. Its stock made from a couple of pork chop bones and scraps will not jell and the pastry will collapse.

Steak and kidney pudding would appear to come straight from Mrs. Beeton, a problematical source. It therefore is bereft of mushroom, oyster, herb, spice, ale or black treacle, a meritorious mystery ingredient.

Gorton’s chicken with cucumber consists of nothing but chicken, cucumber, “olive oil or butter for frying chicken” and stock. At least she does not stoop to water, but the origin of this particular shadow is hard to locate. Gorton does not provide a source for the recipe and the Editor never has encountered anything resembling the dish in print or online, so it is difficult to make the case that it belongs with the British canon.

The closest thing in print would appear to be the series of cucumber kormas conjured by Col. Arthur Kenney-Herbert in Culinary Jottings from Madras but even reference to them entails a bit of a stretch. The lead ingredient is shrimp, but his other options for korma do include just about any other fish or meat, including chicken. Other than it and the cucumber, however, his lavishly spiced and flavored compositions bear no resemblance to the dreary Gorton dish.

7. The system partly repaired.

Her recipe does, however, bare the soul of a good idea. Cucumber, whether cold or cooked, is a prototypically English item and its bright flavor marries well with Rhenish Riesling: You might add some to the stock. You will not want something strong like garlic or even onion to overmatch the cucumber (all the spicing in Kenney-Herbert’s kormas is mild), although a scatter of scallion might suffice, and so would a little body, so strip a leaf from the great Boulestin and fry your chicken in light roux, which counterintuitively works better than dusting the meat itself with flour. These companions convert your chicken and cucumber to an appealing preparation that arguably amounts to something English. Its novelty is no disqualification: Living cuisines evolve.

Notwithstanding the appealing aspects of Gorton’s frequently flawed book, its primary significance lies with the date of publication rather than its shallow depth and narrow breadth. In its time few other authors dared delve into the deep domain of British foodways, let alone take the leap to defend British cuisine.

Notes:

-For a detailed discussion of Orwell on British cooking, see Blake Perkins, “George Orwell and the Defence of British Food,” Petits Propos Culinaires No. 101 (October 2014) 68-86

Sources:

Anon., www.potash.marlboro/node/116 (accessed 28 January 2015)

Audrey Alley Gorton, In Defense of British Cooking: 200 Wonderful Recipes that prove the English CAN cook (Brattleboro, VT 1960)

Blake Perkins, “North and south in both geography and metaphor,” www.britishfoodinamerica.com (11 February 2012)