Our Rural Correspondent sails into history aboard the Empress of Canada.

It is fall 1971 and I am boarding the Empress of Canada in Montreal en route for Liverpool and thus back home to Britain after thirteen months on the Canadian prairies studying for an MA at the University of Saskatchewan. I am about to start research for a PhD degree which will lead, I hope, to an academic career.

The Empress looms before me, a wall of white built for Canadian Pacific on the River Tyne by Vickers Armstrong, her name and birthplace eerie echoes of empire. With a gross tonnage in excess of 27,000 tons she was launched in 1960 by Olive Diefenbaker, second wife of Canada’s Prime Minister. She (the Empress , not Olive) entered service in 1961, plying the Montreal-Liverpool route when the St Laurence is free of ice and, occasionally Liverpool-St. John’s, Newfoundland, when it is not. Out of season she operates as a cruise liner. She is the third ship to bear her name and it is a bit of a mystery why. Both predecessors came to sticky ends. The first was torpedoed by an Italian submarine (while carrying Italian PoWs--well done, Italian navy) and sank off the coast of Liberia in 1943. The second, formerly the Duchess of Richmond , caught fire and capsized under overhaul at Liverpool in 1953. She then was sold for scrap.

The third Empress possesses some impressive, relatively innovative features such as a bulbous bow to limit pitching and full air-conditioning. On launch she was judged spacious, luxurious and speedy; in short, representative of ‘everything that is best in British shipbuilding’. But the Empress had the misfortune to enter service when the golden age of the North Atlantic passenger liner was past. She last sailed the route in November 1971. Sold by CP, she then operated as a cruise ship in various parts of the world and under several different names ( Mardi Gras , Olympic , Star of Texas , Lucky Star , Apollon ). In 2003 she made her last voyage, to an Indian scrapyard.

The Empress

Back to that young graduate student climbing a gangplank in Montreal forty-three years ago: I recall sharing a cabin with several strangers, including a young Guyanese and a number of Canadians heading to Oxford on Rhodes Scholarships. I remember charming passengers, amusing deck games, tension-filled whist drives, glimpses of icebergs and, most of all, rough weather that extended the voyage by a day. I missed several meals with queasiness but have no recollection what was served when I did make it to a dining room which, owing to the rough seas, was often sparsely populated. Fortunately, however, I kept some of the menus (probably to impress my mum). I still have these artifacts to hand so I now can reveal what delicacies CP ships laid before its passengers in late September and early October 1971.

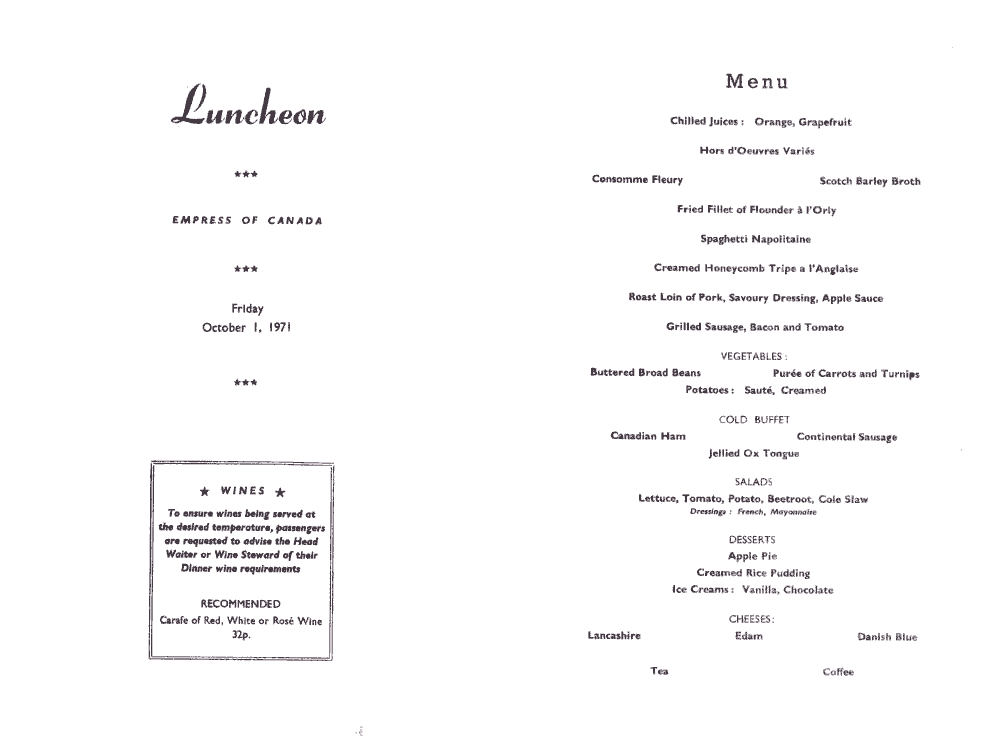

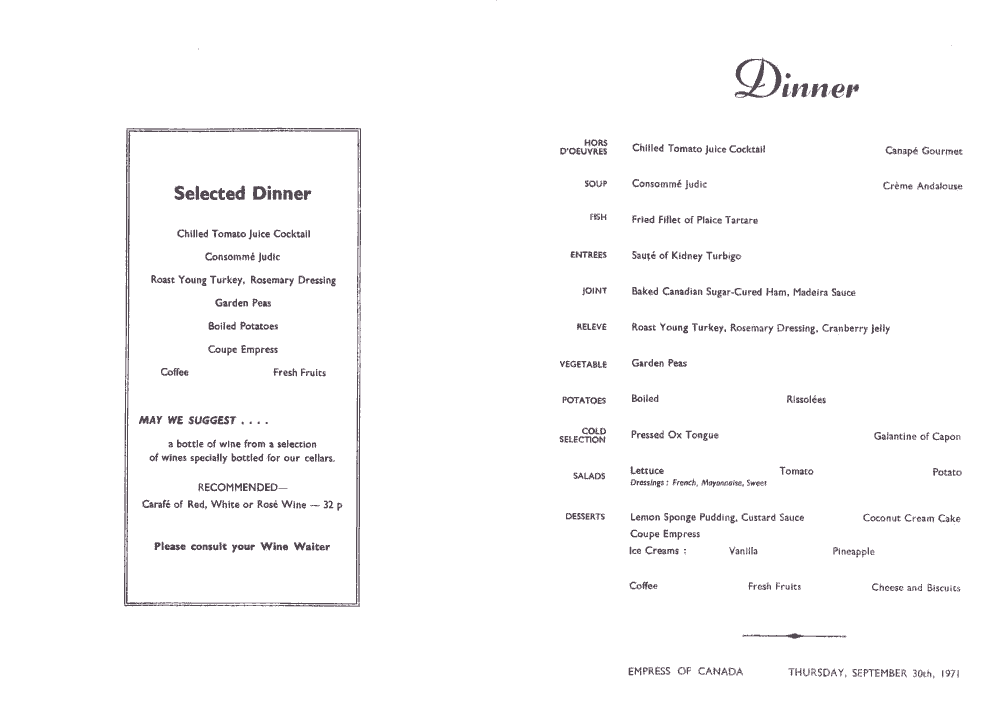

I have six surviving menus; two for breakfast, one for lunch (it is actually ‘luncheon’ on the E of C ), and three for dinner. Each is made of card and bears a date. Breakfast is a single sheet but lunch and dinner open to reveal a centrefold spread. Five of the menus are illustrated with transport themes: a recurring penny farthing for breakfast; for lunch and dinner early locomotives ( Puffing Billy and Stephenson’s Rocket ) and the Savannah (the first ship to cross the Atlantic with the aid of steam power). The front cover of the sixth (Gala Night) menu depicts a fifteenth century feast featuring lamprey and ‘cuttlefish garnished with snails’. I can also spot a whole pig, a lobster, an unskinned hare and the centerpiece, which looks like a live peacock in a hamburger bun. Notes on the rear of the menu observe coyly that lampreys and cuttlefish (with snails) are ‘two of the very few items you will not find on Canadian Pacific menus’. Although this may be something of an overstatement it is true that the CP menus offered an extensive, sometimes mundane but often exotic range of food.

Gala Night cover, with cuttlefish and snails.

Breakfast menus vary little: Chilled grapefruit, chilled juices, fruit compotes and a choice of nine cereals are available every day. There is also broiled breakfast bacon with or without eggs boiled, fried, turned or poached. Graham rolls, breads, toasts, muffins and buns also feature, along with a choice of jams, marmalades and cloudy honey. Pancakes, always of course served with maple syrup are either buckwheat or ‘Scotch.’ Perhaps the most surprising offerings (on different days) are hashed duckling creole and country black pudding. To drink there is tea, coffee or cocoa.

I have only one luncheon menu (for Friday 1 October 1971). It features among other things; consommé Fleury, Scotch broth, fillet of flounder à l’Orly , spaghetti Napolitaine , creamed honeycomb tripe à l’Anglaise . Jellied ox tongue, Canadian ham and continental sausage are available on the cold buffet and cheeses comprise Lancashire, Edam and Danish blue. Consommé Fleury I note is a standard consommé pepped up with sorrel and equal quantities of rice, asparagus tips and peas. Flounder à l’Orly is more prosaic than it sounds, that is, fillets of skinned fish, battered and deep fried, accompanied by tomato sauce. Orly, of course, is a Parisian suburb widely known for its international airport. As one source (no pun intended) observes, the connection between Orly and tomatoes is obscure. I do not order the tripe. I’ve never eaten tripe and beyond an awareness that it comes from the lining of a cow’s stomach, I know little about it. I have been unable to locate a recipe for honeycomb tripe à l’Anglaise . More prosaic offerings are available too, namely, roast pork with savoury dressing and apple sauce, and grilled sausage with bacon and tomato. Accompanying vegetables run to broad beans, puréed carrots, as well as turnips and potatoes sautéed or creamed. Desserts are pretty conventional; apple pie, rice pudding and ice cream. The menu also notes that passengers should advise the headwaiter or wine steward of their dinner wine requirements in order to ensure that they are served at the desired temperature. Recommended wines are carafes of otherwise unidentified red, white and rosé. These carafes (size unknown) are priced at 32p (50c) each.

So to dinner (30 September) with its hors d’oeuvres of chilled tomato juice cocktail and canapé ‘gourmet’ followed by more consommé (this time Judic which, along with several other dishes celebrates the achievements of a once popular French comic chanteuse ) or crème Andalouse soup (cream of tomato with a diced onion garnish). Then it is on to the fish (fried fillet of plaice tartare), the entrée (sauté of kidneys Turbigo), the joint (baked Canadian sugar-cured ham with Madeira sauce) and the ‘relevé’ (roast young turkey, rosemary dressing and cranberry jelly with garden peas and potatoes boiled or rissoles). Kidneys Turbigo consists of kidneys, sausages and mushrooms in a rich sauce. It is often served on toast. The word relevé, I believe indicates a heavier style of cooking. Salads and a ‘cold selection’ (pressed ox tongue or galantine of capon) also are on offer. Desserts include lemon sponge pudding with custard, coconut cream cake and coupe empress (which I had though was a motor car). Coffee, fresh fruits and cheese with biscuits end the meal. Presumably the hungry diner could have ordered all these dishes but the menu helpfully identifies a ‘selected dinner;’ juice cocktail, consommé, turkey (boiled potatoes and peas), coupe, coffee and fruit.

Monday 4 October is Gala Night and that means the gala dinner. We know this is a special occasion because the menu is bigger, the dishes are italicised and the transport motifs have disappeared. This far into the voyage it appears that passengers are perceived to be experienced diners who no longer need to be steered with the ‘selected dinner’ recommendations. There is not even an indication of different courses (hors d’oeuvres, soup, fish, entrée etc). We are all on our own amid an ocean of choice (save cuttlefish with snails and lampreys). Notable starters include croute-au-pot (vegetable soup with bread or toast) and crème à la reine (no consommé on Gala Night). Then it is on to fried fillet of sole ravigôtte , vol-au-vent Regence , a selection of roast meats. Salads and a cold selection, which includes London brawn and pressed ox tongue, are still on offer. Among the desserts are pouding St Jean (bread pudding) with vanilla sauce, Scotch shortbread and coupe jubilee (ice cream and fruit).

Next night, it’s ‘ diner au revoir. ’ So we’ve gone from gala to goodbye in twenty-four hours. The ‘selected dinner’ reappears. It seems that we failed to excel with our gala night choices and after all require guidance. Farewell means the return not only of fruit juice and canapé (Empress) but also of consommé (Imperial) which is chicken-flavoured and served with green peas, asparagus tips and small quenelles of chicken forcemeat. The soup alternative is crème Portugaise (which includes tomato puree, bacon and rice). The fish is fried fillet of flounder with sauce tartare; the entrée (oddly) is scrambled egg on toast with tomato; the joint is roast loin of pork with apple compote; the relevé is roast young turkey with the same accompaniments as before apart from cauliflower au naturel (boiled) rather than garden peas. Pressed ox tongue reappears as a cold selection and desserts include chocolate sponge pudding with custard sauce, Victoria sandwich cake and pear Belle Hélène. As usual, fresh fruit, cheese with biscuits and coffee bring down the curtain. The selected dinner comprises fruit juice, consommé, roast pork with boiled potatoes, the pear BH, coffee and fruit.

Apart from the maple syrup, all this Canadian food appears more Old School English than anything else, the fried fish, the tripe, the roast joints with classic accompaniments, the nursery puddings and not least the French names for English preparations or the pear Belle Hélène. The menus from the Empress represent something of a forgotten time capsule found at a building site or archaeological dig.

The Belle Hélène, for instance, dates to nineteenth century London, where Escoffier created the dessert by poaching pears to serve with vanilla ice cream and hot chocolate sauce. If you would like to make them yourself, simmer peeled, cored and halved pears in a light simple syrup laced with vanilla and lemon juice. Writing in The New York Times during 2004, Nigella Lawson gave permission to use canned fruit in a pinch: “canned pears are certainly not a shameful substitute; just make sure you buy pears in juice, not syrup.” Your Correspondent in turn takes no objection to pears canned in light syrup either. Just give the fruit a squeeze of lemon before draining away their bath.

My twenty-three year old self was well satisfied with the Empress ’s food. It was plentiful, better than mum’s, and a significant improvement on most of the institutional fare I had eaten in recent years. Not surprisingly after 43 years, the menus now seem dated, the culinary equivalent of The Rockford Files , great viewing the first time around but probably not an experience worth repeating.

The Empress menus are nothing if not pretentious. Who now (other than, perhaps, a nudist) would call boiled cauliflower ‘cauliflower au naturel ’? Who now, on dinner menus featuring sponge pudding with custard, roasted joints, brawn, would employ so many Gallicisms? Even so, the compiler missed a trick of two: Why pear belle Hélène rather than poire ; why potatoes, and not pommes de terre ; rissolés ? Still, kidneys Turbigo sounds good. I have found a recipe and intend to give it a try--right now.

Escoffier’s recipe for pears Belle Hélène would appear self-explanatory from our Rural Correspondent’s essay; a recipe for Kidneys Turbigo from our Rural Correspondent appears in the practical.