Offcuts & outliers part 2, featuring decidedly earthy issues, if in different ways and including a 1940 recipe for potted cheese.

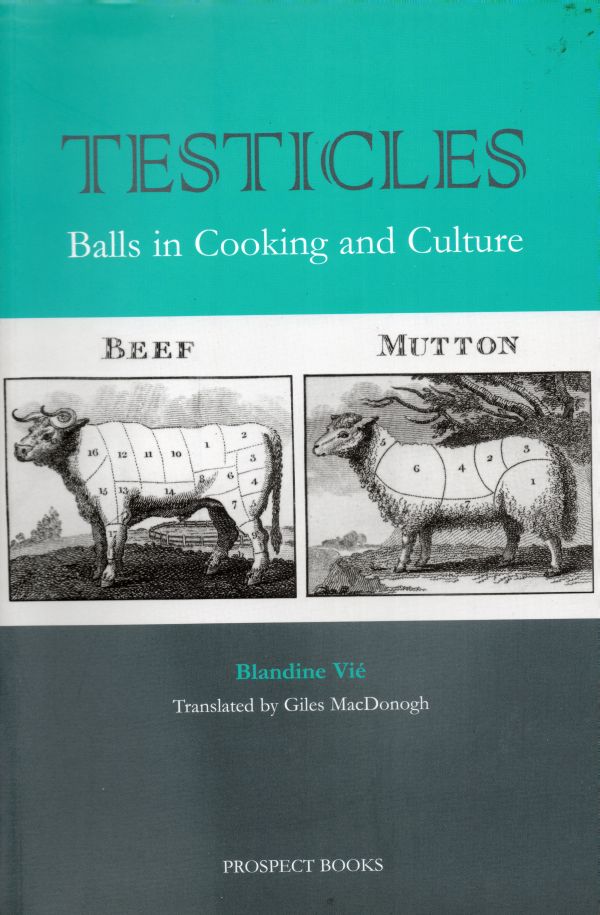

Unmentionable Cuisine by Calvin Schwabe and Curious Cuisine by Peter Ross represent a riot of bugs, blood, brains and balls. Testicles: Balls in Cooking and Culture, as its title infers, confines itself to the balls alone but ranges in broad thematic scope across them. While the author, Blandine Vie, has much to say on her subject, she says it in French, so we are fortunate to have Giles MacDonogh to provide the translation and a number of explanatory annotations.

At the outset he notes something counterintuitive, which may or may not speak to the distinction between French and Anglophone cultures: MacDonogh thinks it says quite a bit. English as a language has many more words than French, including a lot more synonyms. French, however, trumps English in the spectrum of topics subjected to testicular metaphors. That, MacDonogh believes, is because unlike the French, “Britons are embarrassed by their balls.” (Testicles 11)

So far so good, but then he makes an uncharacteristic misstep in marveling that “the French do not share our discomfort. They and other Latins have an [sic: for American readers, British usage] heroic attitude to sex and sexual organs…. ” (Testicles 11) Only gentlemen of a certain age, and mostly of the British Francophile variety, would adhere to so hoary and inaccurate a myth at this point.

Studies identify young British women as the most sexually uninhibited and active people in the world, while many a French father strives, admittedly with mixed success, to keep his daughters incarcerated in the metaphorical chastity belt favored by the mindless evangelicals of the American south.

But perhaps we digress, and unfairly. MacDonogh proves to be a good guide to this strange corner of French culture, noting for example that when Vie writes “testicles have enjoyed (if I can use the word) genuine popularity in days gone by,” there is more than meets the Anglophone eye; there is a buried pun, for she “uses the word jouir,” which “means a much greater form of enjoyment in French--to the degree of orgasmic pleasure.” (Vie 46, 46n)

Vie handles balls in an entertaining if incoherent and extended string of such puns, along with random observations and a jarring dose of pseudo-psychology that includes much discussion of subconscious castration anxiety. The ‘structure’ of the book is odd enough; its ‘Conclusion’ appears at page 46 even though the volume runs to 219 pages. And it may not be altogether reliable. She asserts, for example, that

“at the dawn of the twenty-first century which prides itself on its sexual ‘liberty’--which has little of the gallant about it--the naming and display of male parts remains [sic] taboo, whatever some may say.” (Vie 46)

Not quite taboo any more; The Musee d’Orsay currently is running the large ‘Masculin Masculin’ exhibition devoted to the male nude, including the full frontal rendition, and cable television displays wobbly penises with abandon.

Nor has this American encountered the usage ‘plums’ (“US English: testicles”) in either speech or print.

Sometimes Vie is simply mystifying, a sort of genital structuralist:

“By calling testicles ‘nothings’… you are entering the realm of the ‘not said’--euphemisms--but without being in denial. There is no pejorative connotation. It is just a word that is supremely politically correct (above all when one considers the word being political from the point of view of its etymology as well--it comes from the Greek polis, meaning town). It is a social word, chosen not to shock, but which says everything without appearing to do so.”

This kind of thing belongs only in the Yale English department, and the rest of us may be forgiven for considering it bollocks. Still it is good to learn, and probably should come as no surprise, that ‘fascination’ derives from a Latin synonym for phallus (OK not balls but close enough) or the Romans referred to their castrati as ‘non sunt,’ or nothings.

Testicles includes nearly 100 pages of recipes that few of its readers ever are likely to use.

Apparently they can ration balls, because testicles make no appearance in Vicomte de Mauduit’s They Can’t Ration These. De Mauduit was considered eccentric when his book first appeared in 1940, “to show where to seek and how to use nature’s larder, which in time of peace and plenty people overlook or ignore.” (de Mauduit 7) Not any more, on both counts; in our own sustainable times, de Mauduit sounds prescient and foraging is all the rage.

Like Vie, de Mauduit’s native language is French, but in contrast to her, his prose is brisk and friendly, a feat all the more remarkable because he wrote in English. While we may balk at eating little Cheapside at the dawn of the twenty-first century, evidence suggests that the urban as well as rural English snared sparrows as late as the early nineteenth century. So de Mauduit confides that roast sparrows “are far from despicable;” he treats them like quail. (de Mauduit 56)

Closer to current sensibilities, de Mauduit anticipates the return of newly fashionable cardoons and nettles to our tables, and provides instruction for all manner of pickles and preserves.

His theme overall is much like the posters printed by the British government in anticipation of invasion but happily never used, ‘Keep Calm and Carry On,’ in this case through creativity in the kitchen made possible by living off the land.

De Mauduit reassures his readers in subliminal terms that things will get better and the war will end:

“When the black patterns of winter boughs begin to burst with tender green mist it will be a prelude to better existence, for full-blooming trees will bring us, besides shade and shelter, an abundance of many good things.” (de Mauduit 45)

Mushroom foraging.

They Can’t Ration These, however, is more than a period piece or foraging manual. It offers not only a window on the English cuisine of its time, but also sound, simple recipes useful today. They include a minor miracle, a chowder recipe not from New England that produces something chowdery and even authentic, a feat beyond the grasp of any San Francisco kitchen.

The crawfish boil is positively New Orleanian, trout gets treated to a sprightly court bouillon and, a precursor of aquatic sustainability, the book recommends cooking even the ‘coarser’ finfish, including chub, dace and roach. There is a soothing casserole of cabbage and sausage, cheap treat for a wintry night, and unrationed potted cheese is lighter than most and just about perfect. The simple recipe in full:

“Grate 1 lb. of Cheshire cheese and pound this in a mortar together with 3 oz. butter, 1 saltspoonful of grated mace, a sprinkle of celery salt, and 1 teaspoonful of made mustard. Mix well and press into dry, warm jars. Cover with clarified fat and when this has set screw down the top of the jar before storing it in a cool place.” (de Mauduit 108-09)

Of course, you can use a food processor, while a saltspoonful corresponds to ¼ teaspoon, the proper pinch for a spice as earthily assertive as mace and ‘made’ mustard is simply prepared rather than pure powder.

A beautiful reprint of They Can’t Ration These is available from Persephone Books at a reasonable price. The Editor should note that in reality offal, including balls, remained off the ration books for the duration.

Oddly enough, Fanny Hill’s Cook Book includes no recipe for balls per se, although allusions to them do abound and the book does name a number of recipes after them. Puns and double entendres (e. g. ‘remove your balls from the pot’) abound in this politically incorrect and puerile yet somehow innocent throwback to the heyday of the nude centerfold. The numerous line drawings of big-racked nude beauties use strands of hair, riding crops and lots of other props to shield all genitalia; the sensibility is early ‘70s and, appropriately enough, Fanny’s guide to food first appeared in 1971.

The title of the introduction? “Enter Fanny Hill.” Starters masquerade as “Whores d’Ouvres.” How to discuss sesame breadsticks? “If you are endearingly endowed with a long hard one, covered with warts, stick where it’ll do the most good” (which, it transpires, is into a bowl of cheese and anchovy dip; winky winky, nod nod). (Fanny 6) The Milanese classic becomes recast as “Asso Buco,” and, in case the reader lies at the nether end of the IQ table, gets an explanatory illustration.

Uh huh, we get it….

The authors, a Lionel L. Braun and a William Adams, may be obscure but cannot be accused of subtlety. Their brandade, seasoned incongruously but well with ginger, becomes “Codpieces;” they label their coq au vin “Cock-in-the-Red” so they can indulge in an appropriate (or inappropriate depending on your outlook) prelude to the recipe:

“Woman was the first home appliance that took man’s heavy load upon herself. In fact, Adam was an avid do-it-yourselfer until Eve came. But then, like all couples since, when things went hard for Adam, Eve found she was really up against it. Yet Adam discovered that if he kept bearing down she would run smoothly, except for certain periods when things got especially hot and they both were in the red.” (Fanny 66)

Elsewhere, describing how to make salad dressing: “Dig your whisk into her bowl! Toss her around until she’s creamy… and give her the meat with a vengeance!” (Fanny 15)

A good deal more of this permeates the book, all of it curious, much of it forced. So what is the point? It is, take a seat, good food. It turns out we can accept the boastful authors at their word:

“Every recipe in this book is naughty, suggestive, ribald, licentious, lascivious, and sexy” [Editor’s note: not so sure on that last one].

“The big surprise is that every one of them is also absolutely delicious….” (Fanny frontispiece)

And so they are. The dip of anchovy cheese is laced with capers, chives, mustard and Vermouth; the combination finds a home in both the French and British culinary canons.

Sometimes, however, the authors confuse their cultures. A serviceable enough curry of chicken and tomato, for some reason relabeled “Round the World Stew,” features a woman in the lotus position wearing headgear that would be at home in Vie’s imagination; neither the nude nor her hat has the least to do with India.

For a reason known only to Braun and Adams, they equate the carpetbagger steak with Australia, but “Down Under” is a good variation on the dish that adds mushrooms to the oysters in the pocket of the beef.

It is unlikely that the quality of the recipes accounts for the continued popularity of Ms. ‘Hill’s’ compilation; it must be the kitschy line drawings that render the book expensively collectible. They were drawn by Brian Forbes whom, the Editor has discovered, earned a certain fame for his humorously erotic work, in the “Wicked Wanda” cartoons from Penthouse and similar series elsewhere. There is, as Braun and Adams crow in a distinctly different context, no accounting for taste.

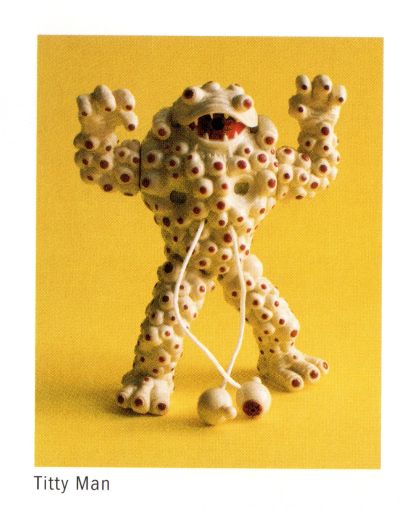

Finally for now to Kenny Shopsin, who courts controversy like a culinary Ted Cruz. If anyone still doubts the intimate connection between sex and food after an encounter with Fanny Hill’s Cook Book, they have yet to encounter Shopsin. In a rare understatement, Shopsin warns that his restaurant “is very quirky.” Among other things, you must, must, converse with the staff and customers, or out you go. If they let you stay you are going to encounter Titty Man too.

He is not the only reference to sex. On the importance of removing the casings before the assembly of his sausage stuffing; “Whether the casing is made of plastic or natural skin, you could cook it forever, and it will never disappear. If you get a bite, it will ruin your meal. It is just an unpleasant reminder of the last time you gave a blow job using a prophylactic.” (Shopsin 190) He recommends Ivory detergent to a customer because it resembles semen; she responds to the advice by quipping that “I hope it doesn’t taste like it, sweetheart.” Needless to say he adores her. (Shopsin 39-40)

Shopsin runs a rather eccentric restaurant out of the Essex Street Market, a WPA wonder in Manhattan, threatened of course with demolition. The place is a sort of New York Uglesich’s, except that it still survives for now.

He likes his customers, but only the ones he chooses to serve. “Customers in this country,” he explains, “have been raised to believe that they are ‘always right.’ Their neuroses are coddled and their misbehaviors are tolerated for their patronage and their money by every restauranteur in America. But not by me. My approach at Shopsin’s is the exact opposite of ‘the customer is always right.’ Until I know the people, until they show me that they are worth cultivating as customers, I’m not even sure I want their patronage.”

Joseph Brodsky and Calvin Trillin pass the test; so do maintenance workers at the New York Board of Education and “a guy named Mark who supposedly had a ten-and-a-half-inch penis. He would have orgies on the roof of his apartment, and the Board of Ed guys would watch them all going at it; then they’d come in and tell me about it.” Shopsin believes in building bridges between the elect, so he is “not averse to saying something like ‘Hey, guys. This is Mark, the guy you see fucking all the beautiful girls on the roof.’” (Shopsin 40-41)

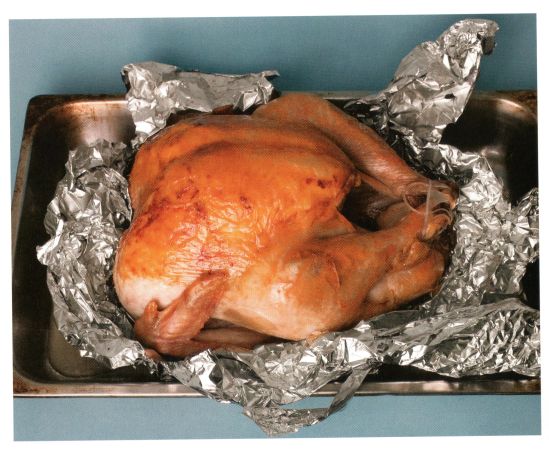

His old roasting technique for turkey reminds him of them. “That beautiful turkey was everything fresh food could be. It was like a girl in her twenties; vibrant, alive, athletic, and gorgeous.” (Shopsin 182)

The halcyon ended, however, at the hands of the New York Department of Health. Shopsin can date the demise;

“…. one day, some prick from the Health Department came in, looked at the turkey sitting up there on its shelf, and said, ‘Is it 140 or 40?’ meaning over 140 degrees or under 40 degrees. That’s the law. Everything in a restaurant has to be either super fucking hot or super fucking cold. Well, it wasn’t either. It was sitting there at room temperature.”

There follows the inevitable act of bureaucratic vandalism, and if Shopsin in his rage mixes metaphors he may be forgiven:

“They took the turkey--that gorgeous brown juicy Norman Rockwell bird--threw it in the trash, and poured Palmolive [Editor’s note: Not even Ivory!] on it. That’s what they do: They put soap or bleach on what they throw away so you can’t just take it out of the trash after they leave and try to serve it. It was such a waste.” (Shopsin 182)

Now Shopsin must store his roast turkeys in the refrigerator, and wistfully notes that as a result nobody gets to ogle them anymore so “I don’t give a shit about their looking brown and beautiful. I just want them to taste delicious.” (Shopsin 184)

By now it should be obvious that Shopsin’s style is a hoot, but the substance of his recipes matches the fun in terms of quality. Shopsin you see is serious, and his roasting method is sound. He sagely reminds readers not to overcook the big bird; an internal temperature of 140° (Fahrenheit) is all you need. People destroy their turkeys “under the impression that they have to cook a turkey to something like 180°--another piece of crap propaganda propagated by the Health Department.” (Shopsin 185)

His cookbook devotes seventeen pages to variations on the burger; to steam one of them, Shopsin recommends a dogfood bowl, and he runs riot with eggs. The creativity continues apace with, for instance, a ‘turkey cloud,’ which is Shopsin’s transformation of Cajun boudin. Out with the rice and pork; in with bread and, of course, his voluptuous turkey. This is syncretic comfort food of a high order.

The biggest innovations may arrive with the soups. As he says, “whether you like them or not my soups are pretty damned clever.” Clever not for its own sake, but because Shopsin hates soup in the traditional style. “I think the worst thing about most soups is that you can’t taste the individual ingredients. If you were to close your eyes and take a bite, you wouldn’t be able to tell what the fuck you were eating.” (Shopsin 125)

Shopsin likes his kind of soup, however, and many start with a color, name or both rather than concept (“I often come up with a name that I like and then invent a dish to go with it.”). His Madras soup started with an old shirt:

“I wanted to name a soup after a madras [sic] shirt I owned in high school. I felt really good whenever I wore that shirt…. This soup has all the colors that were in the plaid: green, yellow, and cranberry. I put some Indian spices in the soup because of the name, but that is not really what the soup is about. It’s really about the shirt.” (Shopsin 136)

Like many of Shopsin’s recipes, this one gets an unexpected fillip of his marinara sauce. African green curry soup, however, does not, and is not African. The curry paste that Shopsin uses is Thai, “but this is a color soup; my intention behind the design was that all the ingredients be green,” and yet he adds peanut butter.

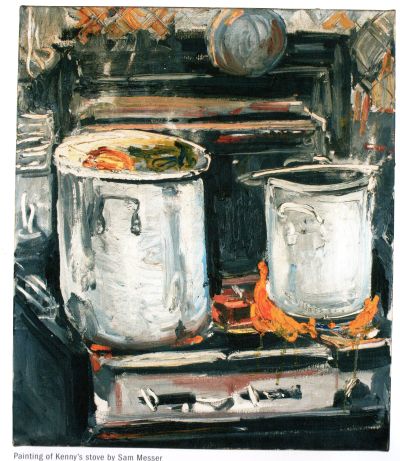

Shopsin is as self-aware as he is idiosyncratic. He grills his chicken on the surface of a gas burner which, he admits, “involves messing up your stovetop.” (Shopsin 127)

Finesse leaves him cold. On Mexican food, he allows that it “can be sophisticated and subtle and it can use all kinds of exotic ingredients, but that is not the Mexican food I am talking about. The kind of Mexican food I like is the kind… based on a foolproof combination of melted cheese, spicy peppers and greasy red meat.” (Shopsin 206).

Practicality will out. Shopsin buys his lefses from a source in North Dakota because making them from scratch “would be more work than its worth. That’s not what my cooking is about.” (Shopsin 6) He no longer makes puff pastry--frozen is fine with him, and the Editor concurs--and “[m]aking beef stock is a real pain in the ass” so he simply adds commercial base to chicken stock with… his marinara sauce. (Shopsin 124)

He prices his soups, expensively, because they are ‘clever’ and take him relatively long to make, “at least four or five minutes of my (almost) undivided attention, which is a lot by my standards.” A bowl that costs him no more than $2 will go for as much as $20.

In the best Animal House tradition, Shopsin chose to name his book Eat Me: The Food and Philosophy of Kenny Shopsin. Go get a copy.

Recipes from the pages of Count de Mauduit, Fanny Hill and Kenny Shopsin appear in the practical.

Note:

‘Lefse’ is a soft Norwegian flatbread, something like a denser flour tortilla. You can do as Kenny Shopsin does and order them from Freddy’s Lefse: 701.235.2056.