A Discussion of Some Hazlitts

William Hazlitt came to a bad end, as if more proof were needed that life is unfair. He died at the age of 52, broke and broken, in a Soho flophouse despite his earlier fame, or notoriety, depending on your point of view. His reputation among modernists both academic and populist has not been much better than his mortal fate, although that may be changing and his vast body of work may immortalize him after all.

William Hazlitt (1788-1830) Miniature by John Hazlitt (1791)

1. Fans of Hazlitt.

By the mid-twentieth century, Hazlitt had become a punchline, but if David Lodge chose him to embody everything that is considered obscure, boring and even ridiculous about graduate studies, Michael Foot and his acolytes in the Hazlitt Society are trying their best to reposition him as the Edmund Burke of the British left. Foot, the former Labour leader whose atavistic election manifesto has justly been called the longest suicide note in political history, may not have been much of a politician, but now in his nineties he remains a likeable and formidable scholar, so if he finds merit in Hazlitt’s work, then we probably should take note. Others are beginning to take notice; for example, Hazlitt currently finds himself on a course syllabus at Sarah Lawrence College of all places.

In Changing Places, among the best of academic comedies along with its deliciously entitled sequel Small World and Richard Russo’s Straight Man, Lodge chooses Hazlitt as the lifelong subject of his most arid and arguably unappealing character, Phillip Swallow (others are wonderfully loathsome; an Oxford don is so awful that he keeps a chamber pot bedside solely because he has the power to prevail upon his desperate graduate student to empty it).

Swallow is a ‘cultured,’ tedious, vain and insecure boor, exemplified by his fixation on the musty Hazlitt and underscored by his philandering with students who hope for his dubious patronage.

Other characters may be equally ridiculous (and true to academic life; Lodge taught for years at Birmingham, which appears as Rummidge University in the novels) but at least they are, and have, some fun. Morris Zapp may be the best. The object of Swallow’s perfervid envy, Zapp used to be ‘a Jane Austen man’ before concluding that all criticism is useless, a revelation that does nothing to stop him from lecturing at conferences of academic critics. He is an American archetype filtered through the British lens:

“ ….Cheryl took an instant liking to him. He was a little larger than life, every line in his figure slightly exaggerated, like a cartoon character; but he seemed to know it himself, and not to give a damn. It made you smile just to look at him, swaggering across the floor of the crowded terminal, with his absurd hat tilted forward, and a fat cigar clenched in his teeth, his double-breasted trench-coat flapping open on a loud check sports jacket. Cheryl smiled…. ” (Small World 115)

Zapp should be an abject lesson to any American trying to adopt British manners--whether or not a Savile Row suit replaces the loud sportcoat, or a plummified overlay muffles our twanging bluster, we can never get it right: He is how they see us anyway--but they find him irresistible.

Zapp may not give a damn that he cuts a ridiculous figure to the British, but that does not mean that he lacks a certain sensitivity (“Give me a kiss,” he said. “A kiss?” “Yeah, you remember kissing. It used to come between saying ‘Hi’ and fucking. I’m an old-fashioned guy.”)

It does not dull his acuity either. Here is Zapp describing his arrival in terms that should get a wry nod from anyone who has traveled in Britain:

“When I landed at Heathrow this morning they tell me that my connecting flight is cancelled, Rummidge airport is socked in by snow. They give me a railroad ticket instead. So I take a cab to the railroad station in London and they tell me the power lines for the trains to Rummidge are down. Great drama, the country paralysed, Rummidge cut off from the capital, everybody enjoying every minute of it, the porters can hardly contain their joy. When I said I’d take a cab all the way, they said I was crazy, tried to talk me out of it. ‘You’ll never get through,’ they said, ‘the motorways are covered in snowdrifts, there are people who have been trapped in their cars all night.’ So I go along the cab rank till I find a driver with the guts to give it a whirl, and what do we find when we get here? Two inches of melting snow. What a country!” (Small World 17-18)

Lodge is equally good on the food; he was writing in 1984, and by then the transformation is apace and the British are eating preparations that are good, if not particularly English other than dessert; steak au poivre and baby squash, “followed by one of her delicious fruit puddings, in which a viscous fruit compote lurked beneath and partly, but only partly, permeated a thick stratum of light-textured, slightly waxy spongecake, glazed, fissured and golden brown on top.” (Small World 58) There is Brie afterwards: We have arrived in the era of Elizabeth David.

slightly waxy spongecake, glazed, fissured and golden brown on top.” (Small World 58) There is Brie afterwards: We have arrived in the era of Elizabeth David.

A brief exchange between Zapp and Swallow embodies their personalities and relative positions. Swallow is hoping for a review of his book, Hazlitt and the Amateur Reader (the title itself is ridiculous), from the prestigious journal that Zapp edits:

“It doesn’t look like the sort of thing Metacriticism is interested in,” said Morris. “But I’ll see what I can do.” He riffled through the pages. “Hazlitt is kind of an unfashionable subject, isn’t he?”

“Unjustly neglected, in my view,” said Phillip. “A very interesting man. Have you read Liber Amoris?”

“I don’t think so.”

That is Zapp’s loss; Liber is pretty good, if undeniably uneven (a semi-epistolary novel, it must be Hazlitt’s strangest work), and it will become apparent despite the running joke that Lodge thinks so too.

Incidentally, Russo has an equally good eye for character and ear for dialogue. When the protagonist’s wife in Straight Man finds him drunk with several naked women in a hot tub, the only question she later asks him something like ‘who was the one with the tits?’ and we know from context exactly why she framed it that way: Shades of Hazlitt here too, as we shall see. Russo is good on the sadly farcical travails of teaching: “Attendance is always sparse on Friday afternoons, especially… when the topic is persuasion. So far, I haven’t persuaded my freshmen that the ability to persuade is an important skill.” (Straight Man 200)

Hazlitt was flawed of course; his politics could be imbecilic (which goes some, but not all, of the way in explaining Foot’s obsessive infatuation with his writings); his personal relationships tended to the appalling; he was socially inept, by turns domineering and intimidated; and his relish for bloody sport like barefisted boxing, while laudable in its time and fascinating for readers today, will strike the squeamish as decidedly incorrect.

2. A fearless libertine.

Hazlitt insisted on the Radical sanctity of the French Revolution notwithstanding the Terror or the fact that the First Republic never allowed an election, and worshipped Bonaparte throughout the nightmare of the Napoleonic Wars. He went on an epic bender after Waterloo.

Arthur Krystal informs us that “[a]lthough he intimated that Petrarch’s unconsummated love for Laura was perfection, since ‘that which exists in the imagination is alone imperishable,’ Hazlitt consummated to a degree that even his friends felt was excessive.” His marriages were contentious and unhappy. Despite Hazlitt’s highminded admiration for platonic love, Coleridge and Wordsworth apparently decried his addiction “to women, as objects of sexual indulgence.” (“Slang-Whanger” 77; citation for both quotations) Lodge reflects one of Hazlitt’s more destructive obsessions when the Swallow character describes the plot of Liber Amoris in barely concealed autobiographical terms of his own:

“It’s a lightly fictionalized account of his obsession with his landlady’s [Ed. note: scandalously younger] daughter. He was estranged from his wife at the time, hoping rather vainly to get a divorce. She was the archetypal pricktease. Would sit on his knee and let him feel her up, but not sleep with him or promise to marry him when he was free. It nearly drove him insane. He was totally obsessed. Then one day he saw her out with another man. End of illusion. Hazlitt shattered. I can feel for him. That girl must have--” (Small World 78)

Now it has become apparent that Lodge knows and likes his Hazlitt too. Others also continue to admire Libor: In 2001, for example, the Irish author Anne Haverty wrote a novel, The Far Side of a Kiss, that retold Hazlitt’s story from the perspective of Sarah, the object of his obsession.

As Krystal points out, Libor is Hazlitt’s fictive “odd duck of a book” chronicling the debacle: “Hazlitt holds nothing back. He describes his obsession unsparingly, omitting no embarrassing detail, including his fear that the girl ‘runs mad for size.’” (“Slang-Whanger” 77)

On this evidence alone, you have to love Hazlitt for his untrammeled Id. But there is more: “Hazlitt once brought a prostitute to his rooms when his ten-year-old son was visiting. [No superego in evidence here either.] Understandably upset, the boy told his mother, who then gave Hazlitt an earful.” (“Slang-Whanger” 78) As if any of this were not sufficiently irritating to his intimates, Hazlitt also savaged (soon to become erstwhile) friends in print; he was as ferocious a critic as he was an insatiable sensualist.

The political writing that interests Foot is in fact good, and consistent in its principled radicalism. Despite his misplaced Francophilia, Hazlitt is no reflexive Anglophobe: “Courage and modesty are the old English virtues; and may they never look cold and askance on one another.” (The Fight 1) The political writing may be the focus of the Hazlitt revival but all of his writing is good: Once you read him, it becomes difficult to fathom how he became an obscure butt of derision. Krystal’s evocation of the style is unbeatable even if his own prose is not:

“Hazlitt takes language for a ride. He doesn’t keep it level and moving at one speed; he guns it, putting it through loops and dives and steep climbs. At the risk of offending Hazlitteans everywhere [They are? We do not know more than one personally.], it bears saying that his descriptive allusions, lengthy quotations, and rhetorical flourishes may in some cases obscure the solid thinking of his arguments. But it is precisely this lack of self-restraint, this willingness to expose himself, this passionate need to explore the world that give his work its flarelike iridescences.” (“Slang-Whanger” 75)

Hazlitt’s style is discursive and delightful rather than tendentious and tedious and, if he is hard on the world, he is (at least a little) hard on himself too, as this passage from The Pleasure of Hating shows:

“As to my old opinions, I am heartily sick of them. I have reason, for they have disappointed me sadly. I was taught to think, and I was willing to believe, that genius was not a bawd--that virtue was not a mask--that liberty was not a name--that love had its seat in the human heart. Now I would care little if these words were struck out of the dictionary, or if I had never heard them. They are become to my ears a mockery and a dream. Instead of patriots and friends of freedom, I see nothing but the tyrant and the slave, the people linked with kings to rivet on the chains of despotism and superstition. I see folly join with knavery, and together make up public spirit and public opinions…. Mistaken as I have been in my public and private hopes, calculating others from myself, and calculating wrong; always disappointed where I placed the most reliance; the dupe of friendship, and the fool of love; have I not reason to hate and to despise myself? Indeed I do, and chiefly for not having hated and despised the world enough.” (Hating 117, 119)

Hazlitt is tougher still in The Indian Juggler. The fact that the juggler is a man of action shakes his confidence:

“The utmost I can pretend to do is to write a description of what this fellow can do. I can write a book: so can many others who have not even learned to spell. What abortions are these essays! What errors, what ill-pieced transitions, what crooked reasons, what lame conclusions! How little is made out, and that little how ill! Yet they are the best I can do.” (Juggler 28)

The purported reason for this disdain is the absence of danger from writing but we do not believe Hazlitt for a second. The juggler risks his life by catching blades; as we have seen, Hazlitt was equally fearless, if not reckless, in his writing, and his meditation on danger could apply equally to his own work:

“Danger is a good teacher, and makes apt scholars. So are disgrace, defeat, exposure to immediate scorn and laughter. There is no opportunity in such cases for self-delusion, no idling time away, no being off your guard (or you must take the consequences)--neither is there any room for humour or caprice or prejudice [irony again here: Hazlitt cannot help himself].” Juggler 31

He literally wrote about everything, including the arts; he, now famously, described the paintings of J.M.W. Turner as “pictures of nothing, and very like,” which is good, for as Jackie Wullschlager explains in prose that is both more prosaic and helpful, Turner’s work is “[m]odern as Claude or Poussin [both of whom he used as foils, Ed.] can never be, both as near-abstract paintings of pure sensation and for their pessimistic vision of man sucked to his destiny in a meaningless whirlpool of history” but also “rooted in classical structure and in a feeling of lived experience.” (FT 15)

The particular interest of britishfoodinamerica, however, lies with Hazlitt’s love of physicality. It is not just the fucking and boxing, but the descriptions of daily life. In The Fight, he revels in the coach ride down from London, the conversation with other passengers in anticipation of the bout and the foods he encounters on the way there (a delicious choice between roasted fowl and mutton chops) before giving us a brilliant evocation of the fight itself.

Sheila Hutchins tells us with her customary lack of attribution Hazlitt “delighted in” a dish of rabbit boiled with onions (Hutchins 177), but none of this actually has much to do with britishfoodinamerica and Hazlitt did not concentrate his considerable literary skills on food. At a certain remove, however, he gave us something in addition to the essays. Apparently his young son William was not traumatized about sex by his precocious encounter with whoredom because he produced another literary Hazlitt, his son William C.

3. Old Cookery Books and Ancient Cuisine.

In 1902 William Carew Hazlitt published Old Cookery Books and Ancient Cuisine. It is primarily about English imprints of English recipes. Carew Hazlitt was a barrister and noted bibliographer, but the underappreciated essays that appear in his bibliographies as prefaces and commentaries on the primary sources also are worthy of attention. The title of Old Cookery Books, one of his bibliographical compendia, is a little misleading; it concerns cookbooks printed from the Middle Ages until well into the nineteenth century. It is no more a mere list of titles than his grandfather’s work is dry or dispassionate.

Unlike his grandfather, Carew Hazlitt was not a political writer, but genes will out and he did not lack a political conscience. In his culinary historiography, Carew Hazlitt conscientiously included musings on the plight of the poor and marginalized through the ages. He finds that Tobias Venner, whose Via Recta ad Vitam Longam was published in 1620, “was not a bad judge of what was palatable” [although he unaccountably disapproves of most fish and considers anchovies in particular “the meat of drunkards”] but ruefully notes that Venner “had no relish for the poorer classes, who did not fare well at the hands of their superiors in any sense in the excellent old days. But he liked the Quality....” (Old Cookery 20) When he discusses historical variations between the foodways of “South Britons” and other British regions, including “those petty states which lay at a distance” from the capital, Carew Hazlitt reminds us that “[t]he dwellers northward were by nature hunters and fishermen, and became only by Act of Parliament poachers, smugglers, and illicit distillers....” (Old Cookery vi-vii)

Despite these concerns, things had improved by 1902 and Carew Hazlitt is optimistic about the march of socialism:

“The redistribution of wealth and its diversion into more fruitful channels has already done something for the people; and in the future that lies before some of us they will do vastly more. All Augaea will be flushed out.” (Old Cookery 13)

Also like his grandfather, Carew Hazlitt is so fond of misdirection that much of his writing elicits a double take. To introduce Old Cookery Books and Ancient Cuisine, Carew Hazlitt explains that

“Man has been distinguished from other animals in various ways; but perhaps there is no particular in which he exhibits so marked a difference from the rest of creation--not even in the prehensile faculty resident in his hand--as in the objection to raw food, meat, and vegetables. He approximates to his inferior contemporaries only in the matter of fruit, salads, and oysters, not to mention wild-duck [!]. He entertains no sympathy with the cannibal, who judges the flavour of his enemy improved by temporary commitment to a subterranean larder; yet to be sure, he keeps his grouse and his venison till it approaches the condition of spoon-meat.” (Old Cookery iii)

Whatever its precise purpose, the passage covers a lot of ground, and Carew Hazlitt was on to something in identifying the linkage between cooking and human development, as the recent publication of Catching Fire by Richard Wrangham indicates.

Wrangham offers his “cooking hypothesis” to explain the anatomical and intellectual evolution of homo sapiens: Cooked food is a more efficient conduit of calories than raw; by cooking their food, humans could shunt the additional energy otherwise required for digestion into brain growth. The need to spend blocks of time tending fires itself had evolutionary consequences because people needed to calm down and cooperate rather than scrabble individually for forage, so humans became relatively less rapacious and irascible. Cooperation ensued, theft was punished and pair bonds developed as cooking became an obligation that females tolerated in exchange for protection. Eventually civilized societies began to evolve.

Wrangham notes that the great anthropologists from Darwin to Levi-Strauss overlooked the role of cooking, and Carew Hazlitt makes a similar observation about historians. In assessing contemporaneous histories of the English people, he marvels that kitchens and gardens got no attention at all. “Yet, what conspicuous elements these have been in our social and domestic development, and what civilizing factors!” (Old Cookery iv) It was a trenchant insight in 1902; as Wrangham in turn marvels about his own thesis, “what is extraordinary about this simple claim is that it is new.” (Wrangham 80)

Wrangham is an interesting figure. Apparently he once persuaded Jane Goodell to let him live au naturel (she priggishly insisted on a loin cloth) with her chimpanzees in their habitat on their diet of raw foods for an extended time, but Wrangham could stand neither the exposure nor the diet and abandoned the project after a couple of days. The experience did encourage him, however, to pursue his thesis that homo sapiens has not evolved to subsist on raw food of any kind. He has found that we spend little time chewing our food compared with other primates, because food that has been softened by cooking is easier to process. Wrangham cites Mrs. Beeton for the same point; two of her six reasons for cooking are to facilitate chewing (“Hurrying over our meals, as we do, we should fare badly if all the grinding and subdividing of human food had to be accomplished by human teeth.”) and “to facilitate digestion.” (Wrangham 71-72) He cites only one other cookbook; the ‘long times’ of the short-lived Beeton continue.

Cooked food also yields more calories. Wrangham observes that chimpanzees spend an inordinate amount of time trying to eat raw meat, an effort that even the most ardent ‘carnivores’ among them often abandoned before consuming a carcass or limb. The process is simply too arduous to sustain them despite their taste for it.

It is not as if Wrangham does not test the thesis; at one point, for example, he also noticed that:

“Chimpanzees have a primitive form of processing meat. By adding leaves to their meat meals, they make chewing easier. The chosen leaves have no special nutritional properties, judging from the fact that meat eaters pick leaves from whatever species of tree is nearest when they settle down to eat their prey. The only obvious rule governing their choice is that the leaf be tough…. Sometimes they even use long-dead leaves from the forest floor, mere skeletons devoid of nutrients.” (Wrangham 118)

Wrangham and some friends (good ones we assume) therefore got together to chew inedible leaves along with raw goat to determine whether the leaves provided enough additional friction to help break down the meat faster than the considerable time it took to chew pure goat. He found that they did.

Back to Carew Hazlitt: as his own discussion of raw meat (duck rather than goat), cooking and cannibalism also indicates, the grandson shared with Hazlitt a penchant for discursion. Carew Hazlitt refers to ‘Joe Miller’ in discussing the Roman epicure Apicius: It is an inside joke for his acolytes. Miller has nothing to do with food but had been the subject of an earlier essay by Carew Hazlitt. Apparently a dour actor typecast in the role of humorless straight man in comedies on the London stage during the eighteenth century, Miller’s was the nom de plume chosen by the author of Joe Miller’s Jests; giving Miller ‘authorship’ itself was a widely comprehended joke and helped the book, first published in 1739, become a bestseller. Carew Hazlitt republished the work in 1871 as The New London Jest Book with a lengthy introduction that explains the joke and otherwise commands our admiration.

Back to Apicius, Carew Hazlitt is too thoughtful a scholar to recycle the conventional wisdom that the epicure actually wrote the first published cookbook, a trap that the editors of the twenty-first century Economist, among many others, have not managed to avoid. Joe Miller serves as an amusing foil in making the point:

“Both Apicius and our Joe Miller died within £80,000 of being beggars--Miller something the nigher to that goal; and there was this community of insincerity also, that neither really wrote the books which carry their names. Miller could not make a joke or understand one when anybody else made it. His Roman foregoer, who would certainly never have gone for his dinner to Clare Market [where Carew Hazlitt bought meat in London centuries later], relished good dishes, even if he could not cook them.” (Old Cookery viii)

Elsewhere the scholarship is equally sound and the insights are similarly original. He bests many modern scholars in noting that the instruction to ‘first catch your hare’ before cooking it, attributed to Hannah Glasse, is apocryphal: “ ….Mrs. Glasse might have almost failed to keep a place in the public recollection, had it not been for a remark which that lady does not make.” (Old Cookery 58-59) Carew Hazlitt also understands what other scholars (notably Gillie Lehmann), only now have begun to realize, that during the 1600s French-influenced Court cuisine coexisted with, rather than supplanted, indigenous foodways--even among the wealthy in Britain.

“Even in the later half of the seventeenth century the old-fashioned dishes, better suited to the country than to Court taste, remained in fashion, and are included in the receipt-books, even in that published by Joseph Cooper, who had been head-cook to Charles I, and who styles his 1654 volume ‘The Art of Cookery Refined and Augmented.’” (Old Cookery 23)

Carew Hazlitt’s selection of ‘old-fashioned’ survivors, however, includes a curious example, the ‘bag,’ or cloth, pudding. Cooper’s seventeenth-century cookbook, he says, includes “a judicious selection…. It is pleasant to see that, after countless centuries which had run out since Arthur, the bag-pudding and hot-pot maintained their ground--good, wholesome, country fare.” (Old Cookery 24) In other passages, Carew Hazlitt refers to the “pre-historic bag-pudding of King Arthur,” “the Arthurian dish… prepared in a bag,” the bag pudding “boiled in a cloth,” “the ancient bag-pudding” and, perhaps inconsistently, “the pseudo-Arthurian bag-pudding.” (Old Cookery iv, 17, 23, 24, 71 and 72)

In contrast, modern writers including Lehmann and Kate Colquohon date the inception of the pudding cloth and ‘bag’ pudding only to the beginning of the seventeenth century. According to them, this most British of preparations was no less innovative than the Court cooking style when it first appeared in England at roughly the same time: “The earliest written record of a pudding boiled in a cloth comes from Cambridge in 1617....” (Taste 123)

England at roughly the same time: “The earliest written record of a pudding boiled in a cloth comes from Cambridge in 1617....” (Taste 123)

Carew Hazlitt gives no source for his repeated assertion that the cloth pudding is an ancient preparation, but he is too good a scholar to discount. Readers therefore are invited to share their research on the origin of the dish.

None of this is to claim that Old Cookery is without mistakes. Carew Hazlitt presciently declares of English food that “[o]ur cookery, like our tongue, is an amalgam” and cites numerous examples. He accurately describes a wonderful publication from 1683, The Young Cook’s Monitor by “M.H.,” as “a really valuable and comprehensive manual.” Old Cookery 25 It illustrates both a distinctive style of English cooking and its cosmopolitan cast; Carew Hazlitt observes that its recipes include “dry beef after the Dutch fashion,” French bread, Italian “frigacies,” Scotch collops and “a leg of pork like a Westphalian ham” but the Monitor also demonstrates that “pies and pastries of all sorts, and sweet pastry, were in increased vogue.” (Old Cookery 25) He states that it and “a sort of companion volume” were printed “for the use of her scholars only” and appealed “to a limited constituency” when in fact the subtitle dedicates the book “to all ladies and gentlewomen, especially those that are my scholars.” (Old Cookery 25; Monitor ‘A2’)

Elsewhere, in decrying the inept execution of English preparations, and notwithstanding the Monitor and other evidence appearing in Old Cookery (including Rare and Excellent Receipts Experienced and Taught by Mary Tillinghast from 1678), Carew Hazlitt insists that “no English school of cookery can be said ever to have existed in England.” (Old Cookery 61) These are minor quibbles, however, and do not detract from his rigorous insight.

Carew Hazlitt spends a lot of time on E. Smith’s Compleat Housewife from 1736 as a good example of the state of the art at the time. He reproduces a number of recipes; some of them involve Medieval practices, like sweetening meats heavily with sugar, that are no longer palatable; some are startlingly modern; and some sound both strange and wonderful. The lamb and mutton preparations are particularly interesting, and so is a cucumber sauce to accompany them. Smith stuffs a shoulder with oysters; marinates chunks of leg in anchovies, cloves, mace, nutmeg and white wine before parboiling and then frying them in an egg wash; and lards a leg with bacon, ‘half roasts’ it and then simmers it in a bath of stock, white wine and vinegar seasoned with allspice, bay, marjoram, savory and scallions. It finally gets sauced with a reduction of the cooking liquor fortified with anchovies, lemon and mushrooms. (Old Cookery 36) We should return to this recipe; look for it.

His coverage of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries generally is good; Carew Hazlitt takes us through the thoroughly English works of Mrs. Glasse (1747), Helene Rundell (1808), Dr. William Kitchener (1821) and Eliza Acton (1845) among others, and notes their broad appeal to everyday cooks as opposed to professional chefs. It bears remembering with him that “Mrs. Rundell is little consulted nowadays; but time was when Mrs. Glasse and herself were the twin stars of the culinary empyrean.” (Old Cookery 61)

Carew Hazlitt’s judgments of particular authors can be remarkably modern. He anticipates Elizabeth David’s rehabilitation of Eliza Acton, using better language, by half a century: long after the book had fallen out of fashion, Carew Hazlitt finds Modern Cookery for Private Families “remarkable for its lucidity and precision” and notes that “the quantities in the receipts are remarkably reliable.” (Old Cookery 65) He also reminds his reader that the plagiarism of cookbooks was rampant before the twentieth century without resorting to David’s judgmental hysteria, although she would have been pleased that Old Cookery Books ignores Mrs. Beeton altogether.

Carew Hazlitt likes the simplicity of Dr. Kitchener and humility of Alexis Soyer; he notes Soyer’s horror at finding a mere cookbook incongruously shelved in a grandee’s library amidst the more deserving works of Locke, Milton and Shakespeare. Carew Hazlitt does not share the chef’s misgivings; he admires Soyer’s Gastronomic Regenerator “in which he eschewed all superfluous ornaments of diction, and studied a simplicity of style germane to the subject; perhaps he had looked into Kitchener’s Preface.” (Old Cookery 64)

Not so Carew Hazlitt himself, but we are none the worse for that.

4. Haslet.

Old Cookery Books and Ancient Cuisine does not mention haslet, but Mrs. Glasse, Mrs. Rundell, Mrs. Acton and others (but not the first edition of Mrs. Beeton) do. Their recipes give us an excuse to exploit the feeble pun. Haslet is a preparation resembling either faggots or meatloaf that originated in Lincolnshire, where it remains popular. According to Helen Gaffney of the British Food Trust, “[f]armers’ wives sent pies filled with haslet to neighbors at pig-killing time” in Northampton. Elsewhere, however, it is no longer a household item, even among the cognoscenti. Neither Elizabeth David nor Jane Grigson published a recipe, and in the otherwise comprehensive River Cottage Meat Book Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall confesses that “I’ve passed on haslet and haggis because although I’ve had excellent ‘in-house’ versions of both from several good butchers, I’ve never attempted to make them myself.” (Meat 425)

Haslet is the kind of thing that the elder Hazlitt would have relished. It is a good, cheap, homely dish, usually still incorporating lesser cuts of pork and stale bread along with onions and sage. The term originally referred to the ‘pluck,’ or organs including heart, kidneys, liver and lung attached by cartilage to the windpipe, usually of a pig. Eventually, haslet referred exclusively to pork, and then to the dish made from the pluck rather than to the organs themselves. It first resembled faggots or savory duck; Mrs. Rundell’s recipe uses the pluck, adds sweetbreads, chopped pork, minced onions and sage, and ties the filling up in caul fat to roast. Other cooks made haslet more like haggis, but with pork instead of lamb or beef and bread or breadcrumbs instead of oats. Most modern recipes for haslet specify ground pork rather than offal so that the term has, in common usage, lost entirely its original meaning. Some sources claim that haslet traditionally is eaten cold; others prefer it hot from the oven.

Variations on recipes for haslet, sometimes called ‘hareselet,’ appear in the practical.

5. Hazlitt’s Hotel.

5. Hazlitt’s Hotel.

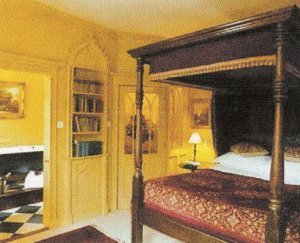

The dump in Frith Street where Hazlitt died, along with two adjoining houses, has become a lovely small hotel called Hazlitt’s, which is fitting enough; he would have approved of assignations at the old address. The hotel is hardly a secret to clever travelers but that does not mean we should refrain from recommending it. The place is not cheap and its staffers are not always competent or friendly, but it is good value by London standards. The benefit of the Soho location is obvious, just across the street from the Dog and Duck, a beautiful little tiled gin palace where Timothy Taylor’s Landlord, one of the better beers on the planet, usually is on tap. Now they have started serving a decent lunch too. Gopal’s Indian restaurant with its tandoori quail is nearby too, along with the venerable and venerated Gay Hussar: Old school Hungarian of course and a traditional haunt of both the Guardian and Labour Party.

It usually is inadvisable to book a single room in a British hotel, and Hazlitt’s is no exception. The Editor once had one on the top floor. A narrow bed, more a built-in prison cot, abutted the wall just inside the doorway; a narrow plank thrown across the small window served as the gesture of a desk. Otherwise its central feature dominated the tiny room.

The Editor’s father always referred to the hopper as a throne, and in this case the reference is not metaphorical. The toilet sat framed in a massive, carved gothic cabinet a step up from the floor. It had a five-foot pedimented chairback and was encased in a clear, glassy cube; you would not need to strain much to feel like one of Francis Bacon’s screaming popes in there. The lack of privacy would not be a plus for assignations, let alone business meetings, unless the principals were coprophiliac. (On that note, a digression: William Carew Hazlitt cites a Medieval stanza from Piers of Fulham: “A mallard of the dunghill is good enough for me/With pleasant pickle, or else it is poison. pardy.” (Old Cookery 72)) It is a room that combines the inappropriately grandiose with the meanly uncomfortable in overlapping contexts, although the setup is hysterically amusing to children and that is worth something.

Always get a double at Hazlitt’s.

Sources.

Kate Colquohon, Taste: The Story of Britain Through its Cooking (New York 2007)

S.K. Dearmont, Hazlitt’s (unpublished ms. 2009)

Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, The River Cottage Meat Book (London 2004)

Helen Gaffney, “The West Midlands, Warwickshire and Northamptonshire,” British Food Trust (www.greatbritishkitchen.com)

M.H., The Young Cook’s Monitor (London 1683)

Anne Haverty, The Far Side of a Kiss (London 2001)

William Carew Hazlittt, The New London Jest Book (London 1871)

Old Cookery Books and Ancient Cuisine (London 2008; orig. publ. 1902)

William Hazlitt, The Indian Juggler, in William Hazlitt On the Pleasure of Hating (London 2004)

William Hazlitt, Libor Amoris, or the New Pygmalion (London 1823)

William Hazlitt on the Pleasure of Hating (London 2004; orig. publ. in The Plain Speaker 1826)

Arthur Krystal, “Slang-Whanger,” The New Yorker (18 May 2009)

Gilly Lehmann, The British Housewife (Totnes, Devon 2003)

David Lodge, Changing Places (New York 1979)

Small World (New York 1995)

Richard Russo, Straight Man (New York 1997)

E. Smith, The Compleat Housewife (London 1734)

Mary Tillinghast, Rare and Excellent Receipts Experienced and Taught by Mary Tillinghast (London 1678)

Richard Wrangham, Catching Fire (New York 2009)

Jackie Wullschlager, “Radical Dialogue,” Financial Times, 26-27 Sept. 2009, “Life & Arts” 15